Framing Resilience

“Do not judge me by my success, judge me by how many times I fell down and got back up again.”

— Nelson Mandela

When the power goes out at an airport, resilience will be tested. In November 2021, two airport power outages on opposite sides of the country impacted thousands of travelers. The first occurred at Phoenix Sky Harbor Airport in Phoenix, Arizona, nd the second event happened less than a week later at Raleigh-Durham International Airport in North Carolina. Both were caused by humans (Fox 10 Phoenix, 2021). Both events tested resilience.

Scenarios such as those power outages highlight the need to be resilient. But what is resilience? This article explores various definitions of the term. It also discusses information sources and some case studies that demonstrate approaches to becoming more resilient. Finally, it offers some tips about managing available resilience information and tapping into those resources.

Both the Arizona and North Carolina power outages can be instructive. Not surprisingly, unexpected power outage events delay flights and cause panic and frustration. Outage events highlight some essential lessons about the concept of resilience. Those lessons teach us how we can bounce back from adversity. The takeaways range from deeply personal to organizational.

The stories of those outages and their inevitable stress and suffering made me think: What if there was an available toolkit that organizations and individuals could use to be more resilient? Where might one find such a toolkit? What would be in it? What would be in an individual person’s toolkit compared to the kit for an airport authority or a Department of Defense unit? The answer to those questions sparked an information quest that led to this article.

In Phoenix, the Monday Morning quarterbacks agreed that many steps could have been taken to prevent that kind of event. That idea of prevention is a concept at the heart of any resilience discussion. Looking deeper into the Phoenix event, the root cause was a problem with the maintenance process. According to Arizona Public Service, the commercial power company for the airport, “APS crews were performing maintenance on the electrical system that serves Sky Harbor in preparation for the upcoming busy travel season when a failure occurred in a piece of equipment called a switching cabinet. We’re looking into what caused that failure” (Phoenix Central News, 2021). Ironically, preventive maintenance, often a key contributor to resilience, was the culprit in Sky Harbor’s painful outage.

Less than a week after the Phoenix event, it was Raleigh-Durham Airport’s turn for an unexpected power outage. Again, human error was the culprit: RDU spokeswoman Crystal Feldman said a cleaning crew spilled a large amount of water. It seeped through a floor and onto an electrical box, tripping the system for Concourse C. “This was a freak accident that happened,” Feldman said. “We apologize for the inconvenience. This is absolutely unexpected.” (WRAL.com) An apology is a weak recovery tool for the weary traveler trapped at the airport. Conversely, information about the cause of adversity is a powerful component of resilience.

Defining Resilience

“If I had only one hour to save the world, I would spend 55 minutes defining the problem, and only five minutes finding the solution.”

— Albert Einstein

Power outages at places such as Phoenix and Raleigh are rare. But they pack a punch. When an airport is impacted, there is often a domino effect across the nation. Delayed or canceled flights create a spiderweb of effects at far-away locations that have nothing to do with the root cause.

We can learn a great deal about resilience by doing a case study about any power outage. The good news is that every event illustrates resilience tools that will help in the future. The bad news is problems are not limited to human error. Our energy infrastructure faces significant hazards such as weather events, earthquakes, fires and terrorism. The ugly news is that we don’t know how unprepared we are until disaster strikes. Therefore, it makes sense to maximize the number of available resilience resources. Consider the lifeboat on a cruise ship: It’s nice to know it is there, but passengers don’t pay much attention to lifeboat operations until the ship is going down. At that moment, two things are vitally important: The first is that somebody has been paying attention, and the lifeboat is ready. The second is that somebody is there to organize the lifeboat activity during the chaos.

The lifeboat image hints at one aspect of resilience. But as with the blind men attempting to describe an elephant, there’s a lot more going on there. At its core, any definition of resilience involves bouncing back from events such as airport power outages. The idea is to take a punch and get back in the fight. If one applies those concepts to valuable power and water resources, a definition of energy resilience emerges. Presidential Policy Directive 21 provided an early description of what energy resilience means. In a nutshell, the document called it the “Ability to prepare for and adapt to changing conditions and withstand and recover rapidly from disruptions.” (White House, 2013) Five years later, the National Defense Authorization Act defined energy resilience as “The ability to avoid, prepare for, minimize, adapt to, and recover from anticipated and unanticipated energy disruptions in order to ensure energy availability and reliability sufficient to provide for mission assurance and readiness, including mission-essential operations related to readiness, and to execute or rapidly reestablish mission-essential requirements.” (NDAA, 2018)

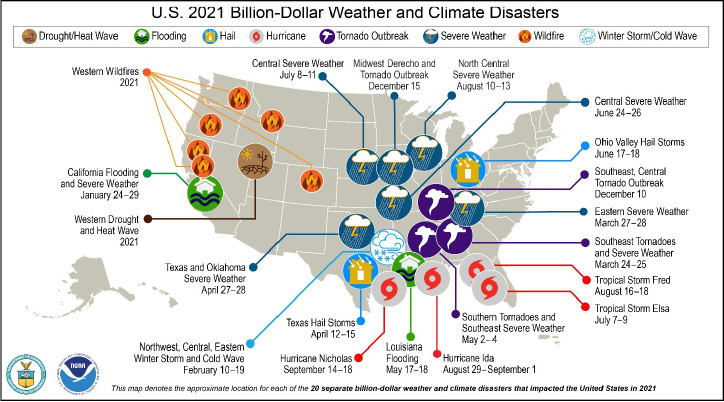

Resilience is cloaked in the classic military idea of readiness. A foundational aspect of readiness is understanding threats. In the energy infrastructure world, threats range from tornadoes to terrorists. No matter your politics about global climate change, the costs are real: The National Centers for Environmental Information found that “In 2021, there were 20 weather/climate disaster events with losses exceeding $1 billion each to affect the United States. These events included one drought event, two flooding events, 11 severe storm events, four tropical cyclone events, one wildfire event and one winter storm event. Overall, these events resulted in the deaths of 688 people and had significant economic effects on the areas impacted. The 1980-2021 annual average is 7.4 events (Consumer Price Index-adjusted); the annual average for the most recent five years (2017-2021) is 17.2 events (CPI-adjusted).” (NOAA, 2022) If the only threat were weather, resilience would demand responding to multiple punches.

Once you understand what resilience means to you, the trick is to figure out how to get some.

Curating a Personal Resilience Toolkit

“It is really wonderful how much resilience there is in human nature. Let any obstructing cause, no matter what, be removed in any way, even by death, and we fly back to first principles of hope and enjoyment.”

— Bram Stoker, Dracula

My son recently watched a movie called Ready Player One. A key character in the movie was “The Curator.” The Curator provided key clues to a mystery at key times in the story. He demonstrated an enviable high-tech ability to virtually show you anything there was to know about his museum. As I listened to some of the banter in the movie, I wished I had my own resilience curator. What would a curator have available for resilience seekers? Where would he start, and how would the information be organized? Those questions inspired me to build my own resilience library. Then, after seeing many available resources, I set about organizing my collection. It was then that I realized that the knowledge managers of the world play a critical role in our survival. Curators and librarians are heroes.

Knowledge management heroes provide us with a venue to seek the answers to our questions. Sometimes they answer questions we did not even know we had. In an age where Google has become a verb, it helps to have somebody who can point you in the right direction. I set a goal to curate some of the gobs of energy resilience information that is out there. But I soon realized it was a massive undertaking. I am building the airplane while flying it. The upshot of that revelation is an understanding that there is always more available. If a toolkit can help one person find a resilience resource, it is worth the curating effort. Resilience information can be like a snowball rolling down a mountain. Each new information source is filled with references to other resources. The trick is to find the ones that make sense for you. This article describes some of the places to find your answers.

Preparing For Disaster

“Experience is the name we give to our mistakes.”

— Oscar Wilde

So what can we do to better prepare for disaster? How can we become more resilient? When one considers recent disasters, it is helpful to assess the experiences and teaching moments from a resilience framework: What worked out? What didn’t? Are there common preparatory actions that individuals and organizations can take to improve their ability to bounce back? I was intrigued by the idea that there should be a place where one can go to find the answers to these types of questions. So I did what any pilgrim would do at the start of a journey: I Googled “Energy Resilience Toolkit.” That action led to joy and frustration. Immediate joy came in the form of a resource called the “U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit,” managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Program Office. Created in 2014, it frames resilience as a five-step process. NOAA recommends resilience seekers:

- Explore Hazards: Identify the things that can cause you harm.

- Assess Vulnerability and Risk: Determine the likelihood and impacts of harmful events.

- Investigate Options: Develop potential courses of action to mitigate damage.

- Prioritize and Plan: Evaluate the costs and benefits of your options.

- Take Action!

In addition to outlining their five steps for Climate Resilience, NOAA provides a useful list of references and some case studies. Maybe most importantly to some, NOAA provides a list of potential funding sources for improving resilience. While the focus is on climate, the approach applies to the closely related topic of overall energy resilience (NOAA, 2022).

A good business practice is to find an organization that does what you do and benchmark it. The United States federal government is one of the best benchmark opportunities in the energy arena. The Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP), hosted by the Department of Energy, provides a wide array of resources and training opportunities for energy resilience. FEMP has a large pool of experience to draw upon: “With more than 350,000 energy-utilizing buildings and 600,000 vehicles, the federal government is the nation’s largest energy consumer. Energy used in buildings and facilities represents about 40% of the total site-delivered energy use of the federal government, with vehicle and equipment energy use accounting for 60% of that energy. (FEMP, 2022) The FEMP team acts as a clearinghouse for information flow from all that experience.

Mandated by law, the FEMP hosts utility working groups and various in-person and virtual events to share their knowledge. FEMP is just a few clicks away on your computer keyboard.

The Department of Defense is a great place to find more narrowly focused energy resilience tools. The Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Sustainment has a large library of references and guidance documents. The resources are generally rooted in a scary tenet from the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) that the homeland is not a sanctuary. The 2022 NDS promises more of the same, with the word “resilience” prominently featured in the DoD fact sheet about the new document. It makes sense that defense planners would value the idea of resilience. Type “OSD Energy Resilience” into your favorite search engine to find a summary of the Defense Department’s thoughts on the topic. You will also find a timeline showing the evolution of defense philosophy from “energy security” to “energy resilience” and beyond.

Of course, if the OSD team has a philosophy about resilience, the individual armed services staffs feel the need to define it better. The U.S. Army has three documents that provide insights and strategic guidance for energy resilience. The first is the Army Climate Strategy, published in February 2022.

The climate strategy outlines the service’s approach to adapting to the changing climate and pursuing greenhouse gas mitigation strategies. Their approach forms a nexus where initiatives like electric vehicles could both reduce impacts on climate change and provide a resilient power source for installations.

The strategy includes a high-level line of effort to enhance Army installation resilience. Deeper into details, the Army Installations Strategy illustrates how the enterprise will maintain energy and water systems that will be “resilient, cyber-secure and efficient.” There are 26 key references at the end of the document. Some of those references provide more insights into resilience planning and response. There would likely be more if the alphabet had more letters! The December 2020 Army Installation Energy and Water Strategic Plan is a third, even more-detailed Army resource. There are 33 reference documents listed at the end of that plan. The plan describes how the energy resilience goal ensures that the Army has the required energy and water to complete critical missions under all conditions.

The U.S. Navy released an Installation Energy Resilience Strategy in February 2020. Links about Navy energy resilience are located at the website for the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Energy, Installations and Environment. A nice feature of that particular website is a list of resources at other DoD locations. That demonstrates the importance of a joint fight, whether it be on a traditional battlefield or in the utility world.

The Air Force has similar guidance documents, some of which are referenced on the Office of Energy Assurance website. AF Leaders published their Installation Energy Strategic Plan in January 2021. Like other defense planning documents, it links to the National Defense Strategy and provides a flight plan for achieving mission assurance through energy assurance. The plan pursues three goals:

- Identify Enabling System Vulnerabilities

- Improve Resilience Planning

- Ensure Resilience Results

Resilience Case Studies

“I made it through the rain and found myself respected by the others who got rained on too and made it through.”

— Barry Manilow

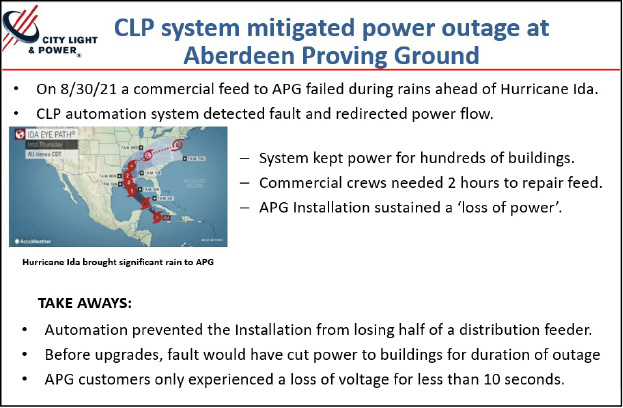

The increasing number of events that test our resilience has a bright side. Each time we ride out a storm or recover from an unexpected threat, we learn more lessons. Wise leaders share their lessons and embrace the feedback from others. Concerning DoD sites, several new microgrid projects are in various stages of development. There will doubtlessly be lessons from the construction and testing of the systems. There are also other smaller examples of tools that can be applied, such as automation and looping.

Best practices in the industry reveal proven measures to reduce three significant aspects of an outage. Those aspects are frequency, duration and scope. Each of those measures contributes to reliability differently:

- Frequency: When a system has less frequent events, the overall annual number of outages is reduced. In the case of Hill AFB, the number decreased from 43 events in 2015 to 12 in 2021. But reducing the number of raw outages alone is just one component of resilience.

- Duration: Shorter outages translate to less impact on the customer. System automation and improved crew response times reduce outage duration times.

- Scope: The number of customers impacted by an outage is an important resilience factor. The goal is to limit the extent of the impact from a single event. For example: If five outages affect 10 buildings each, 50 customers lose power. Compare that to three outages of 20 buildings each, where more customers (60) are affected by a lower number of events.

An ideal system improvement would reduce all three components of outages. A metric that captures all of those components is “Customer-Minutes Interrupted,” or simply customer-minutes. That customer-minute value is a key component in two reliability indices tracked by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), the duration index and the availability index. The mission of the power provider is to maximize the availability and minimize outage duration. A perfect system would achieve those goals by applying all available resilience tools, but that comes at a cost. Considering budget pressures, the cost of the resilience tool is almost as important as its availability. Analysis of performance indices and available improvement tools can help power distributors consider key questions about the resilience of their systems. The first question is: “How much reliability is adequate from the customer’s perspective?” The second is “Where should a utility spend its reliability dollars to optimize efficiency and satisfy customers’ electricity requirements at the lowest cost?” The following paragraphs provide an example of investments that balanced those two questions at an Air Force installation in Utah.

One example of improved resilience is the electrical distribution system’s performance at Hill Air Force Base, north of Salt Lake City, Utah. The system provides an insightful case study for reducing the number and impact of power outages. In 2015, one year after taking ownership of the system, City Light & Power engineers planned projects and capital investments to renew the electrical distribution system. They introduced automation and other selected tools to reduce the frequency, duration and scope of power outages. The selected investments were based on the classic Asset Management approach. A team determined what they had, assessed conditions and developed a prioritized plan to maintain or replace components that needed improvement.

Six years later, the number of outages was down 72%, and the customer downtime from outages was down 87%. While many variables affect the operation of an electrical system, outage, frequency and cumulative duration are most telling. Those two measures speak volumes about the impact of improved system maintenance and investment. Table 1 illustrates the dramatic effects that system investments can make. While there are many uncertainties with power distribution, the table shows a trend of improved system performance over time.

A short illustration about the IEEE duration index may be helpful here. Customer minutes represent the overall impact of an event. A two-hour outage affecting 10 customers would tally 1,200 customer minutes, and a shorter 30-minute outage affecting 50 customers would tally 1,500 customer minutes. The System Average Interruption Duration Index, aka SAIDI, tracks the trend of customer minutes over a given interval, usually a year. Figure 1 illustrates the trend of reduced outage impact for the data at Hill AFB. For an outage duration metric, down is good!

There was nothing magical there beyond a sense of ownership, component recapitalization and some focused automation technology. The key was that leaders paid attention to performance metrics, identified trends and applied some available tools. The result was a significantly improved electrical system resilience.

Another case study of resilience for an electrical system is at Aberdeen Proving Grounds. There the government chose to privatize the system in 2012. The new system owner and the Aberdeen team partnered to plan and execute a total rebuild of much of the installation’s electrical distribution backbone. Thanks partially to the new components and controls, the average outage duration decreased from 300 minutes in late 2013 to 100 minutes in early 2022. The system uses new technology to bounce back more quickly from significant events like when Hurricane Ida roared up the East Coast in August 2021.

Resilience Tips and Tricks

“That which does not kill us makes us stronger.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche

World events from 2020 through early 2022 tested individual and social resilience. A global pandemic stressed many systems that provide the food, shelter, transportation and entertainment that humans count on for daily life. Significant weather events tested infrastructure — especially power systems. Finally, the war in Ukraine provided lessons for future generations about surviving and bouncing back. The lessons from all these events are available through many sources. This article highlighted some of the information resources for energy resilience. While this is just the tip of the information iceberg (and we do not have a virtual metaverse curator available at our command), there are several places we can go for guidance. This concept applies whether we need help preparing for an event, responding to an emergency or recovering from a knockdown.

Seven recommendations for improving resilience include the following actions:

- Keep a log of the energy resilience resources available to you. Update it frequently.

- Adopt best practices and lessons learned. Many are shared on resilience websites.

- Use asset management tools to track the condition of your system components.

- Track the performance of your systems and invest in the highest priority requirements.

- Share your resilience stories.

- Track communities of practice such as the Society of American Military Engineers Resilience Group. There are tremendous opportunities to benchmark and share lessons.

- Be a resilience beacon. For example, practice disaster preparedness at home and store flashlights and water.

Conclusion

“Our greatest glory is not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall.”

— Confucius

Championship coaches have often talked about how their team showed great resilience. Usually, the point is that team members overcame adversity to achieve their goals. Sometimes the coaches thanked the people who paved the road for good performance. Those people provided the resources and the training to enable success. Resilience is like that. Resources are available to help prepare for, respond to and recover from adverse events. There are resilience coaches out there, too.

For almost any adversity your team will face, others have faced a similar situation and bounced back from it. We are all called to be resilient at some point. Will you be ready?

Richard Houghton is the Installation Manager at Hill Air Force Base and the DoD Energy Resilience Operations Director for City Light & Power, Inc. He leads Hill’s Electrical Utility Privatization team. He is also a liaison to the Department of Defense for Resilience Operations. Rich retired from the Air Force in June 2014 as the MAJCOM Civil Engineer, Air Force Global Strike Command, Barksdale AFB, Louisiana. He is a Life Member of the Society of American Military Engineers, and he first joined SAME in 1988. A native of Rochelle Park, NJ, Colonel Houghton earned his Bachelor of Science in Engineering degree from the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, NJ, where he was also an All-Conference pitcher on the baseball team. He was commissioned into the Air Force through the Reserve Officer Training Corps in 1987.

References

Chowdhury and Koval, “Current practices and customer value-based distribution system reliability planning,” in IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 1174- 1182, Sept.-Oct. 2004, doi: 10.1109/TIA.2004.834075.

Department of the Army, Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Installations, Energy and Environment. February 2022. United States Army Climate Strategy. Washington, DC.

Federal Energy Management Program, About the FEMP, April 2022: https://www.energy.gov/eere/femp/about-federal-energy-management-program

Fox10 Phoenix, https://www.fox10phoenix.com/news/power-restored-to-phoenix-sky-harbor-airport-after-outage-impacted-american-southwest-flights

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters, 2022.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit, 2022: https://toolkit.climate.gov/#steps

Phoenix Central News, https://www.abc15.com/news/region-phoenix-metro/central-phoenix/power-restored-at-phoenix-sky-harbor-airport-delays-likely-to-continue-through-monday-evening

United States Code, Title 10 — Armed Forces — Govinfo.gov: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/10/101#e_6

White House, Presidential Policy Directive 21: Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience (PPD-21) Feb. 12, 2013.

WRAL.com website, Nov. 12, 2021: https://www.wral.com/cleaning-crew-blamed-for-rdu-power-outage/19976796/