By Byron Foster

On July 1, 2019, Utah adopted the 2018 IBC (based on ASCE 7-16), which brought with it several very significant changes to local seismic practice. These changes, which are summarized below, are impacting geotechnical and structural engineers and their clients. They were discussed in greater detail by several presenters at a continuing education workshop on June 10, 2019, at SLCC.

When you become familiar with these changes, you need to make sure that you are looking at the final version of ASCE 7-16 and also the December 2018 supplement.

The primary changes include:

- A penalty for not having detailed site investigations

- Changes to the site factor (Fa and Fv) tables

- Near-fault site definitions

- A vertical ground motion approach (where site-specific procedures are not used)

- Site-specific seismic assessments for Site Class D or E when S1 > 0.2 and for Site Class E when SS > 1.0 unless exceptions are taken. There is a significant impact for longer period structures.

From discussions with local engineers who have started to use the new code, it appears the largest changes may be:

- Penalties for assuming a Site Class D, or not having measured site properties to define the Site Class, should drive projects to obtain good measured properties routinely.

- From structural engineers who have locally compared ASCE 7-10 and the old seismic maps to ASCE 7-16 and the new seismic maps, the ground motions seemed to have increased significantly.

- However, since the intent of the code change was to address the unconservative estimates of ground motions for longer periods (taller buildings), it is not clear yet what the impact of the exceptions will be on building design/cost.

- Cost increases from the new ground motions used for design could be as high as about 5% of the building costs.

- The most significant change will probably be that for almost all of the populated areas of Utah (which are typically Site Class D or E with S1 > 0.2g), the owner will have to have either a site-specific seismic assessment conducted, or the structural engineer will have to use one of the three “exceptions” (potentially penalizing building costs).

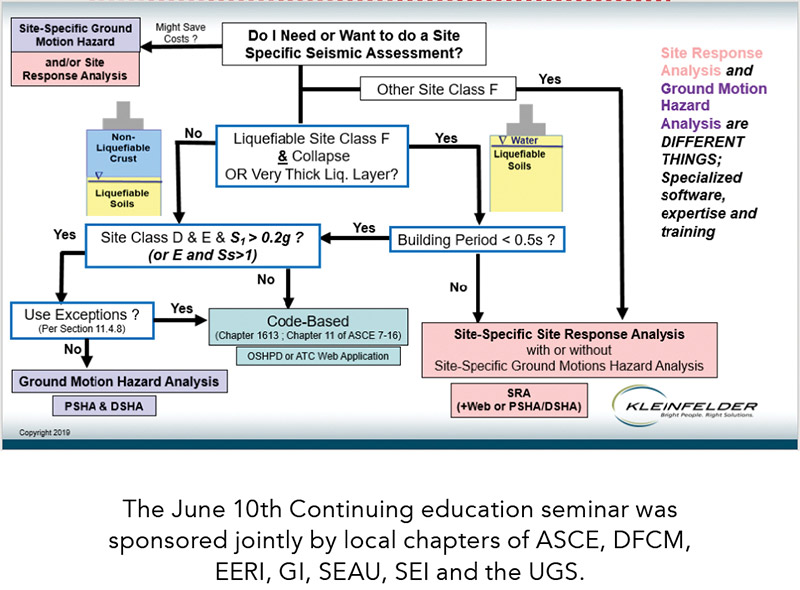

There has been some confusion in Utah regarding what constitutes a “site-specific seismic assessment.” For example, the spectral acceleration values obtained from the USGS website do NOT constitute a site-specific assessment. Similarly, a Deterministic Seismic Hazard Analysis (DSHA), by itself, is not a site-specific assessment. A DSHA is only a check on the Probabilistic Seismic Hazard Analysis (PSHA).

There are two types of site-specific assessments defined under the Code:

- A Ground Motion Hazard Analysis, which is composed of both a PSHA and a DSHA for a check, and

- A Site Response Analysis (SRA)

In deciding which method is needed and who should do the work, you should consider the following factors:

What is required by IBC 2018 and ASCE 7-16?

What is the importance of the structure? Hospitals, police stations, and other important public buildings should receive particular attention.

- Is the building period > site period?

- Do you have measured values for the shear wave velocities in the soil?

- Is the rock depth several thousand feet deep, but you only have information on what the soils are in the upper 100 feet or so?

- Does the firm conducting the work have experience passing rigorous peer review by seismic experts for the method that will be conducted?

While IBC 2018/ASCE 7-16 provides detailed design approaches, we are still learning from designing and pricing alternatives so that we can know when it will make sense for the structural engineer to use an exception versus using the results of a site-specific seismic assessment. In the meantime, given the potential for significate schedule delays and added costs from the exceptions, we must all continue to inform our clients about the need for these new studies.